How products exploit our biases

In light of the US regulator suing Adobe for 'hidden cost' subscription plans.

What is Bias?

Wikipedia:

Bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is inaccurate, closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair.

My interpretation: It’s a judgment with little or no logical rationale behind it.

Actually, all of our judgments and decisions are limited by the facts we have, which often rely on small data samples. However, biased conclusions tend to carry more weight despite lacking logical or statistical justification.

Why are they subject to exploitation?

There are two reasons that make them ideal tools for marketing teams to undermine rational decisions:

They are bugs in our behavior that we are not usually aware of—blind spots in our consciousness. This allows them to be used to manipulate our actions. Moreover, some experiments have shown that knowledge of these biases may not prevent their effects.

They are common among the majority of people, making them effective for a wide target group, largely independent of gender, race, education, and social status.

There are many biases and a variety of their applications, but I have decided to limit this article to a few common examples.

Decision fatigue

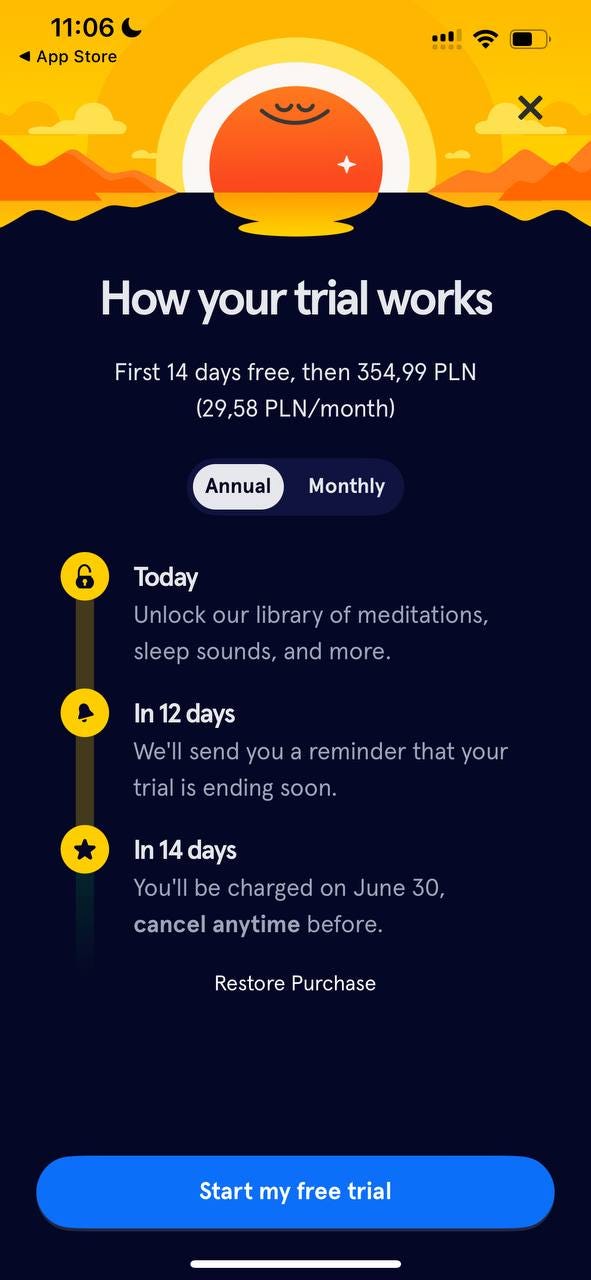

When it comes to subscriptions, services tend to eliminate all possible barriers and frictions to make signing up effortless.

Free trials. Pay-as-you-go. Pay-upfront. One click and you’re in.

What’s on the other side? What if you no longer want or need it? Would the experience be as frictionless?

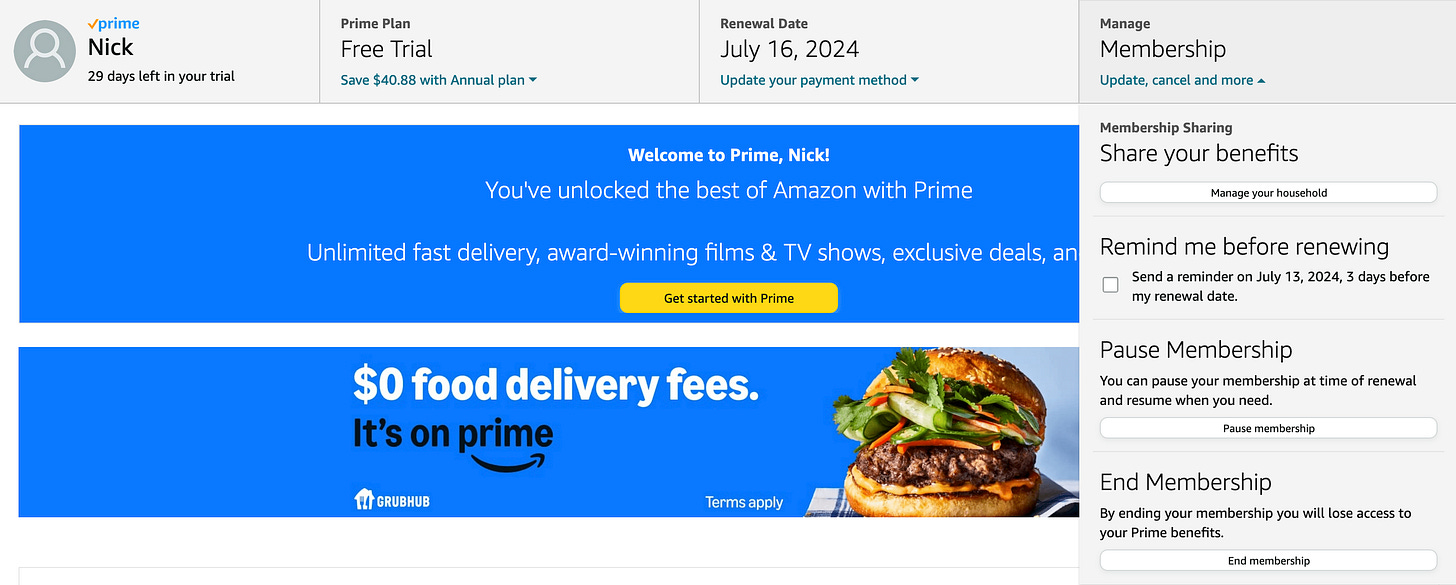

Let’s try to cancel an Amazon Prime subscription.

Starting from the profile, it’s pretty clear—I tap on Manage My Membership.

Then I’m getting to the dedicated section. As I need to cancel the subscription, tapping on the dropdown in the Membership section.

Now it’s unfolded—I’m clicking on End Membership:

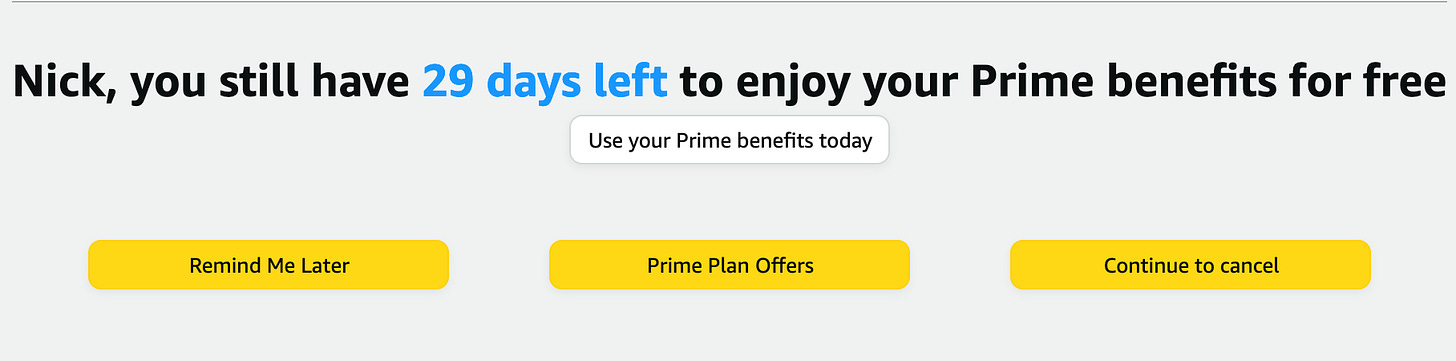

Here, Amazon is trying to steer me away by providing four choice options. I could try to use my benefits if I haven’t done that before.

Amazon may remind me later. Honestly, this option is a bit confusing—I don’t know what will happen next. Will it remind me about the trial end? Probably.

It’s also possible to check other plans. This option is for price-sensitive users who find the value/price ratio isn’t optimal. They might consider annual subscriptions to cut the cost, which benefits Amazon as they receive more money in advance.

Finally, what I was looking for—Continue to Cancel. This should cancel the membership.

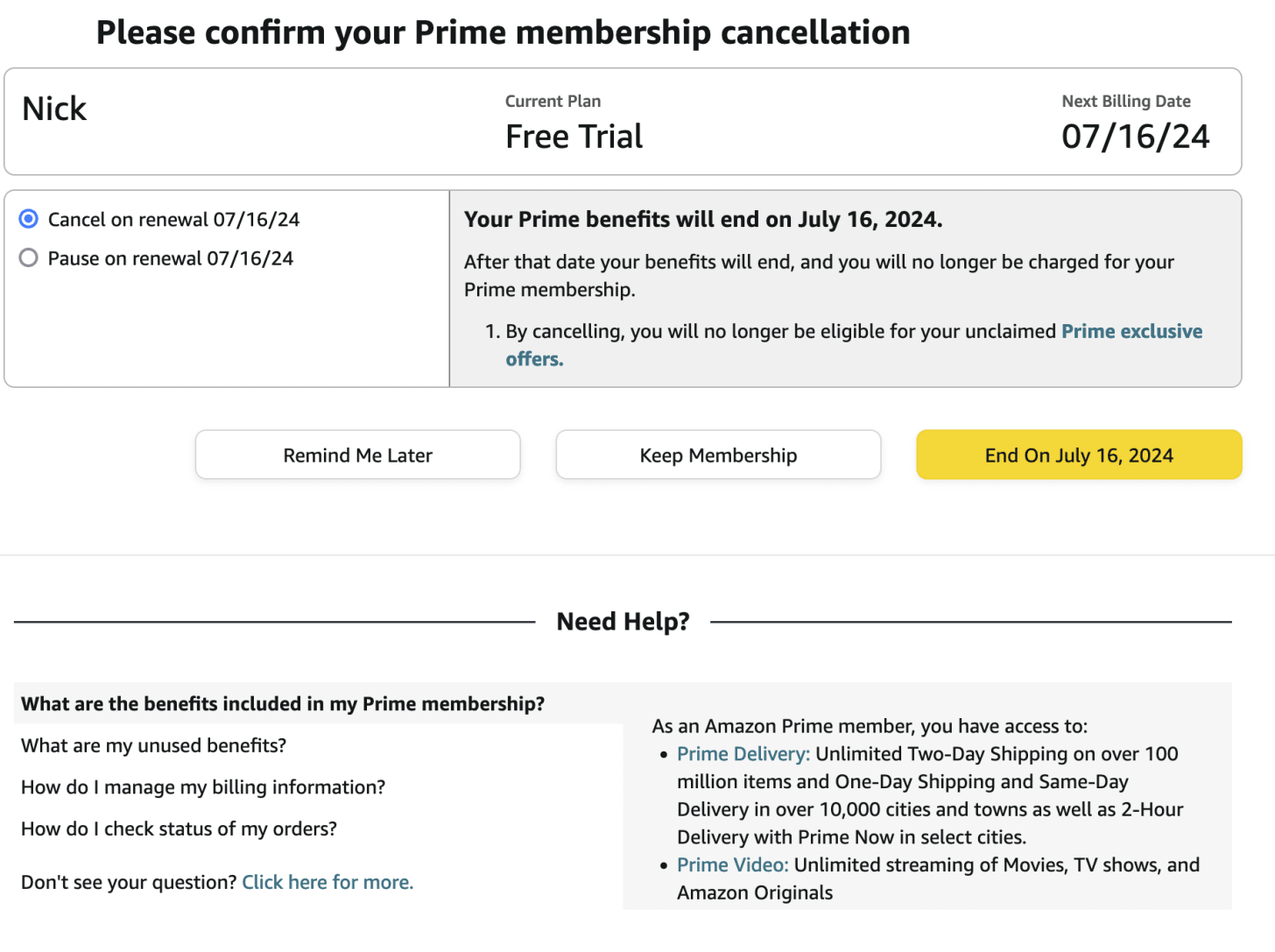

Nope, not yet. Amazon still has some words to say.

It kindly reminds me of the benefits I’m losing by canceling my membership. This is a good example of exploiting my Loss Aversion bias.

And again, there are plenty of options to choose from: feel free to pause or cancel the renewal, keep your membership, ask Amazon to remind you later, or end your subscription.

Tapping on the last button finally gets us to the anticipated result.

Why are there so many steps to perform such a simple action? Because Amazon is trying to prevent users from canceling.

A multitude of steps induces Decision Fatigue—a feeling of being overwhelmed by the number of decisions to be made.

Our attention and cognitive ability are limited resources, and we tend to optimize their utilization. Having many options to choose from may affect our initial intention, even when each decision is quite simple.

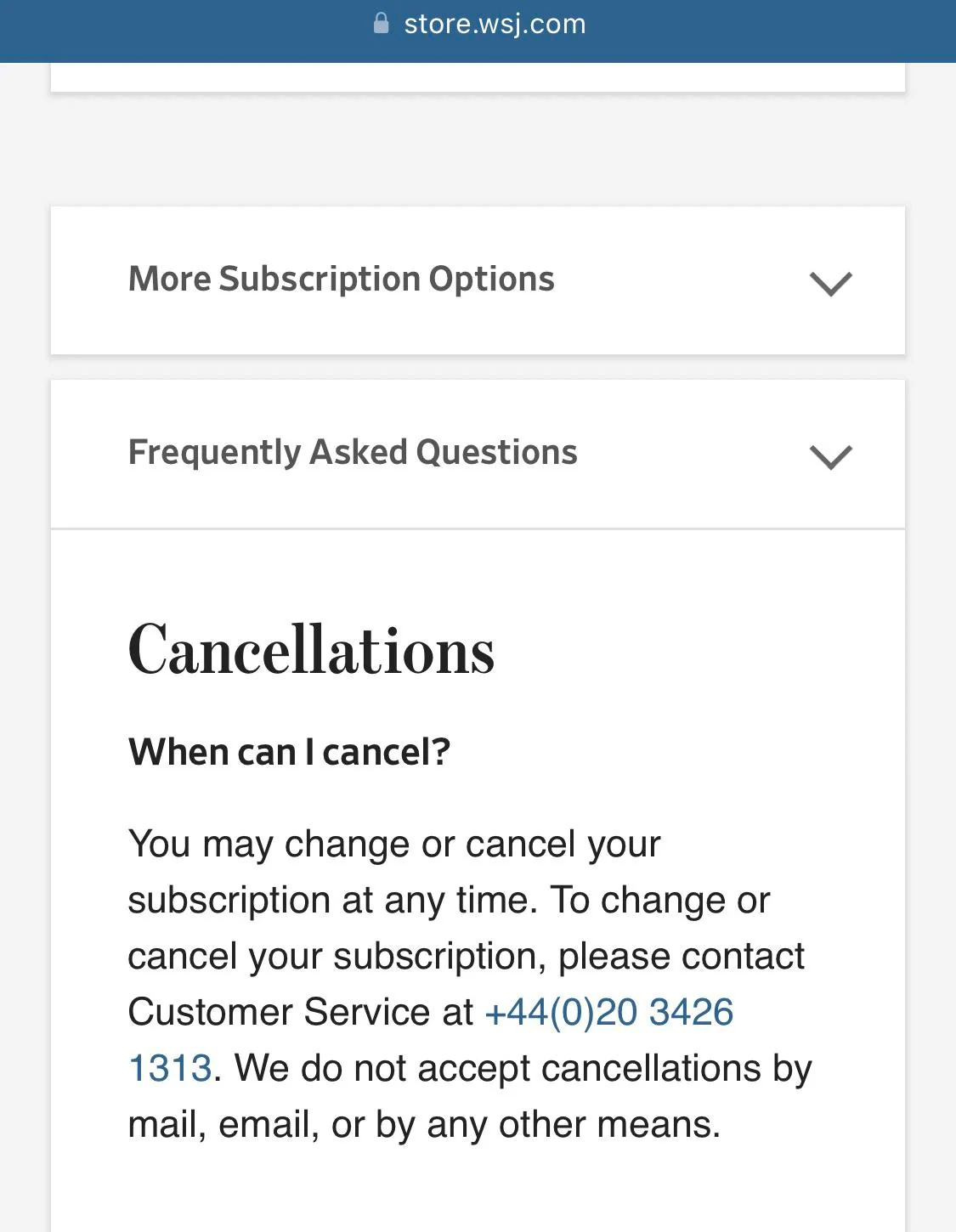

But we can’t blame Amazon in a world where the Wall Street Journal previously forced them to require a call to customer service for membership cancellation. I’m not kidding.

Scarcity bias

Only 10 spots left! Early-bird offer! Offer for the next 59 minutes only!

Marketing teams are extremely creative in using our fear of missing out or, speaking in terms of biases, Scarcity.

Because of this, the brain tends to perceive things as more attractive if their availability is limited.

There are multiple explanations for this effect.

From my point of view, the most reliable is that some deep layers of our brain developed when our ancestors lived in a world where everything was extremely limited.

Missing the chance to consume things as quickly as possible could lead to a lack of resources in the future.

Today, we live in a new world where overconsumption is an emerging problem. Recalibrating one's wishes toward a more moderate version might be very beneficial.

Anchoring effect

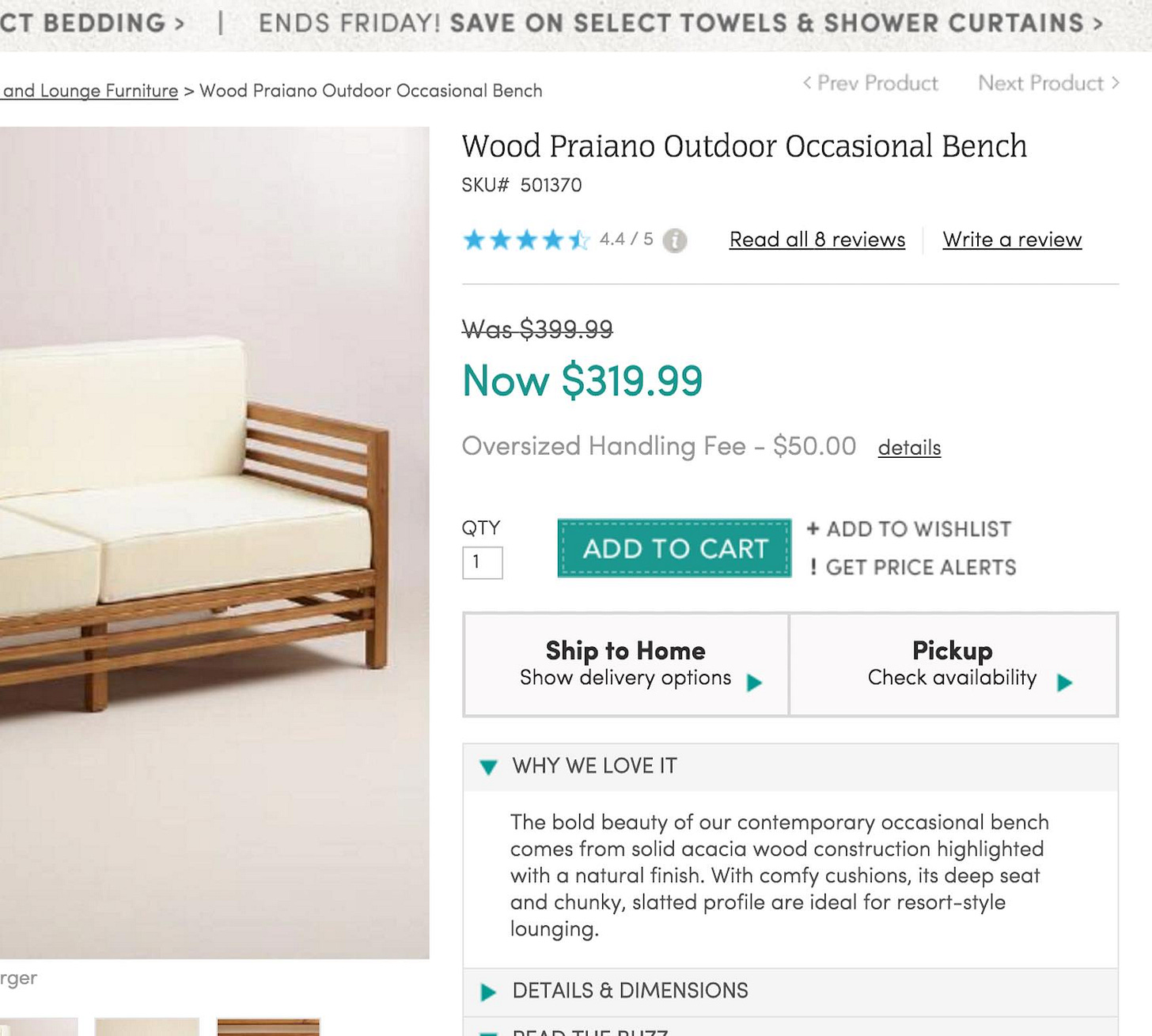

Discounts.

Arguably, they are one of the key sales drivers. I love them, and a lot of people do.

Sad news: some of them have a close relationship with the Scarcity bias.

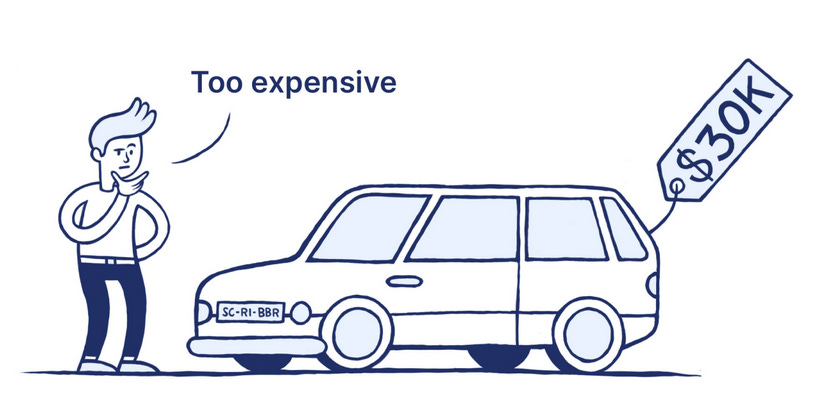

What if I offered you a car for 30K?

Would you capture it or just let it slip? That might seem like a good price, but you could also think it's too expensive.

Now, imagine I told you the car actually costs 60K, but I'm willing to sell it to you for just 30K!

Sounds like a much better deal now, right?

This tactic, often used in retail, is called Anchoring bias.

Our minds tend to use the first piece of information we get as a reference point. Regularly, it causes irrelevant purchase decisions.

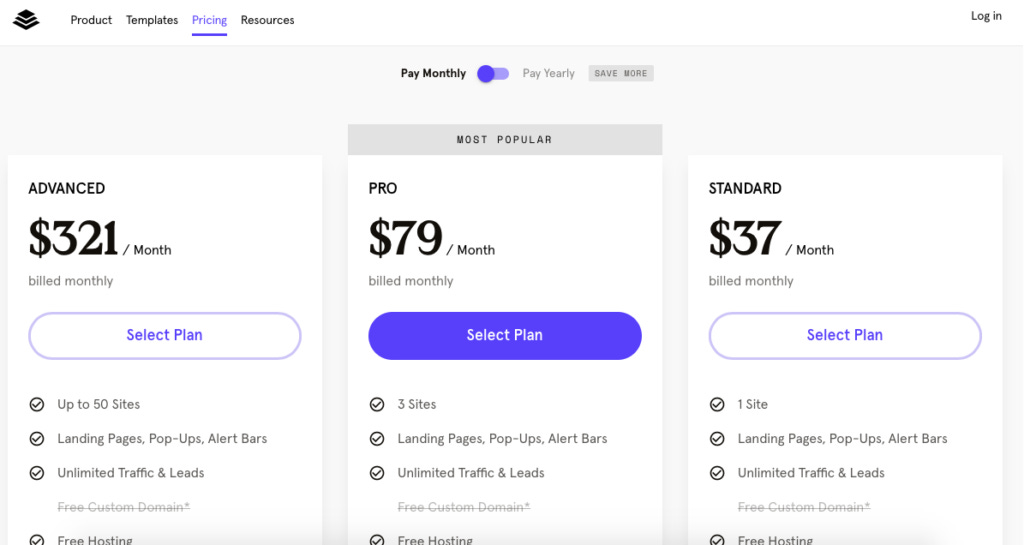

Another common example is presenting multiple options to make one of them look more appealing.

End notes

I hope that knowing these techniques will help you be more aware of your consumer decisions.

Let me know if you’re interested in exploring more of them.

Stay rational!